Chapter Conservation Profile: San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area Chapter (SFBAC) of SCI has developed a strong relationship with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife (CDFW), assisting the agency with several initiatives that support SCI’s mission to protect the freedom to hunt and promote wildlife conservation. This partnership between the Chapter and CDFW has been strengthened through financial support from the Safari Club International Foundation’s (SCIF) matching grants program, as the Chapter’s work aligns closely with SCIF’s commitment to wildlife conservation, outdoor education and humanitarian services.

Over the past ten years, the SFBAC has raised more than $750,000 to help CDFW advance their mission of managing the Golden State’s diverse fish and wildlife resources for their ecological values and recreational use by the public. This amount of financial support is unmatched by any other sportsmen group in the Golden State, making the SFBAC one of the most influential conservation groups in California. The majority of these funds were produced by auctioning off hunting opportunities and tags for some of the states’ most coveted big game species, including mule deer and elk.

Most recently, the Chapter provided two robo-deer decoys for game wardens to strategically deploy during anti-poaching operations, as the life-like deer help catch would-be poachers shooting from roadsides, with spotlights or out of season.

In addition to aiding wildlife law enforcement efforts, the SFBAC has supported several research projects focused on California’s big game species – most notably mule deer.

The SCI Foundation has established itself as one of the leading mule deer research organizations in the country, having spent more than $500,000 on mule deer research over the last 20 years. That number doesn’t include additional support from SCI chapters, many of which share a similar commitment to addressing mule deer conservation issues to meet modern management challenges – perhaps none more so than the SFBA Chapter.

California is home to two species of mule deer – the Columbia black-tail and the California mule deer. Columbian black-tailed deer inhabit a large portion of far western North America, from northern California through the Pacific Northwest and coastal British Columbia. However, beginning in the late 1990s, data collected by the CDFW began to indicate that the California herd had declined from an estimated high of about 2 million in the 1960s.

The SFBA Chapter has poured considerable resources particularly into studying the Jawbone Tuolumne deer herd on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The herd has been the subject of research dating back to the 1950s, when a telemetry project first studied the herd’s movement. Interestingly, that project was led by Starker Leopold, whose father, Aldo Leopold, is widely considered to be the father of modern science-based wildlife management in North America.

This early research coincided with a broader decline of mule deer throughout their range for reasons that remain somewhat unknown but likely include increased drought, expanding human development, changes in forest management, expanding energy development, and increased predation in areas where carnivore populations are growing.

The Columbian blacktails, especially in California, have also been affected by widespread infestation of two exotic louse species – African Biting louse and Fallow Deer louse, both of which are now relatively widespread across the West including California, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Both species of parasite are believed to have been brought to America via exotic species from overseas but their exact origin in the United States remains unknown.

African Biting lice have been found throughout the United States for decades, but the presence of Fallow Deer lice was first was first discovered in 2009, when biologists from CDFW went to investigate reports of a mysterious dead mule deer.

When CDFW launched an in-depth study to explore the impact that lice were having on the black-tailed deer in Stanislaus National Forest, the SFBA chapter stepped up to provide more than $20,000 to help make the project possible. Support for the research was further leveraged by the Safari Club network, with another $8,000 from the SCI Golden Gate Chapter and additional contributions from SCIF’s conservation matching grant program.

Since CDFW made the commitment to studying lice-infested deer, over 600 deer and elk statewide have been captured to provide hair and blood samples. Some of them were also affixed with GPS collars to determine how movement and habits may also be impacted.

Initial monitoring made it evident that lice infestation was causing deer to dedicate a substantial amount of time and energy scratching and biting, leading to what is now known as Deer Hair Loss Syndrome. The loss of insulating hair and the energy expended on self-grooming made deer more susceptible to harsh winters at high elevations. They also became more vulnerable to predation by bears, mountain lions, and coyotes. Anecdotal evidence supported these claims with stories of people being able to walk right up to deer more concerned with alleviating their discomfort than about personal safety.

Perhaps the most important finding documented through this research was the notion that the soil and deer browse in the area had reduced selenium content compared to browse in other mule deer ranges. Selenium is a naturally occurring element that is toxic in large amounts but also an essential nutrient for most living organisms. Selenium deficiencies have previously been detected in other game species like pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, and elk. Research has shown that supplemental feeding of selenium pellets can resolve the issue.

Not only do low levels of selenium increase fawn mortality in mule deer, it was also believed to be exacerbating the deer herds’ newfound lice issue by weakening immune systems and leaving deer more susceptible to additional infestation. The CDFW began dispersing selenium based mineral blocks throughout mule deer range and other feeding grounds were treated with selenium pellets in an attempt to increase nutritional value.

To further study potential treatments, CDFW affixed several of the deer they live captured throughout the study with ear tags filled with insecticide to fight against the lice – a practice more commonly used to protect cattle and other livestock from similar pests. Deer captured during the study were also given booster shots of selenium. The research showed that the insecticides and supplemental selenium successfully worked to prevent and reduce louse infestation, relieved stress on deer and helped reduce the lice’s negative impact.

However, these solutions are not broadly applicable and further research would be needed to determine how to best leverage these localized solutions to have a broader impact. The good news is that even though mule deer populations in the area are still considerably lower than what they were in the 1960s and 1970s, the population has stabilized to the point that it may be increasing again and the herd remains capable of supporting hunting opportunities.

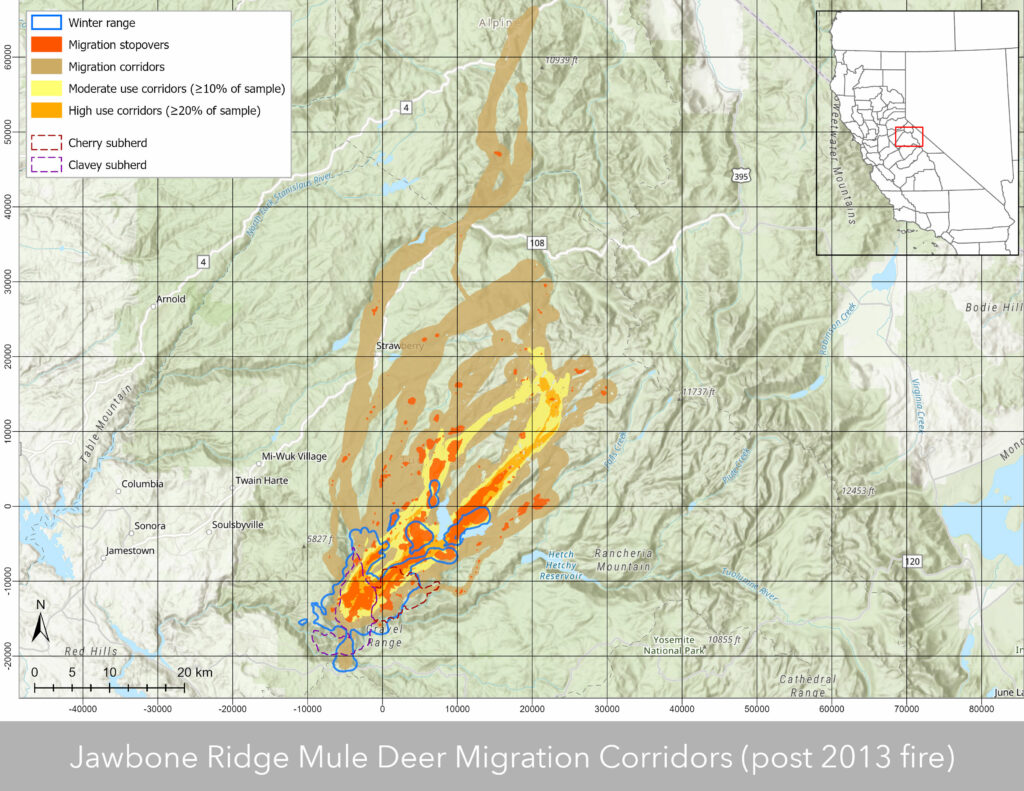

In addition to supporting the aforementioned study, the SFBA Chapter has provided CDFW with significant financial support to gain a better understanding of the same herd’s habitat and migratory and foraging patterns, particularly as they relate to forest response to wildfires.

Migration routes and seasonal habitat preferences were monitored through the use of GPS collars and radio telemetry – similar to the first research project that focused on the herd in the 1950s, although technology has advanced significantly since then.

(photo courtesy of CFDW)

The Jawbone deer herd relies on several types of vegetation, including oak woodlands, coniferous forest, meadows and grasslands, chaparral and riparian corridors that occur in a mosaic or quilt like pattern with variable stages of growth and forest age classes represented. They also rely on areas where cover and forage are in close proximity to free water.

The project allowed CDFW to identify several key risks to the region’s mule deer herd as part of a broader Environmental Impact Statement for wildfire recovery the region, which in turn has helped shape management strategies that have contributed to the stabilization of the herd. Those risks include degradation of shrubby habitat because of a lack of fire or active management resulting in reduced forage quality, grazing competition with cattle, reduced presence of oak trees leading to a limited acorn mast, and the encroachment of conifer forests into native meadowlands.

The SFBAC also has made considerable contributions to the other core missions of SCI Foundation– education and humanitarian efforts in their state. SFBAC has been a longtime supporter of the agency’s hunter education program, with volunteers helping coordinate quarterly hunter education courses and has a long history of involvement with SCIF’s American Wilderness Leadership School, the Sportsmen Against Hunger program, and with organizing hunting and fishing trips for wounded veterans. Chapter members have also been active with SCI advocacy efforts at the grassroots level in their state, rallying grassroots support on the ground in California to help push back against an attempted legislative trophy importation ban that would have had devastating consequences for rural communities and wildlife populations across Africa. Their efforts in part lead to the legislation’s downfall.

The SFBA Chapter encapsulates the full scope of what SCI and SCIF stand for, from protecting the freedom to hunt and promoting wildlife conservation throughout their state. They provide educational opportunities to help ensure future generations have an appreciation for hunting and the great outdoors and share their bountiful harvest of wild game with those in need. The SCI San Francisco Bay Area Chapter has cemented themselves as First for Wildlife and First for Hunters in California.