Mountain Memories

Record-Book Chamois Finally Gets Its Recognition After 50 Years

By Ed Fortunato

I looked through the scope and placed the crosshairs of my Springfield 1903 A3 rifle slightly behind the shoulder. As I settled myself, I soaked in the scenery and reflected on the journey that brought me here. I confirmed with my guide which chamois was the trophy, slowly exhaled into the freezing mountain air, and squeezed the trigger. The chamois fell at the report.

The next 52 years would prove to be a story and journey as memorable as the hunt itself.

In 1972, I was an Army captain returning from my second tour in Vietnam. I requested Germany for my next assignment. I was 28 years old, raised in the Bronx and had never been to Europe. I thought it would be a great family experience and was pleased when I received orders to Heidelberg, Germany, a picturesque medieval town on the Neckar River, undisturbed by WWII.

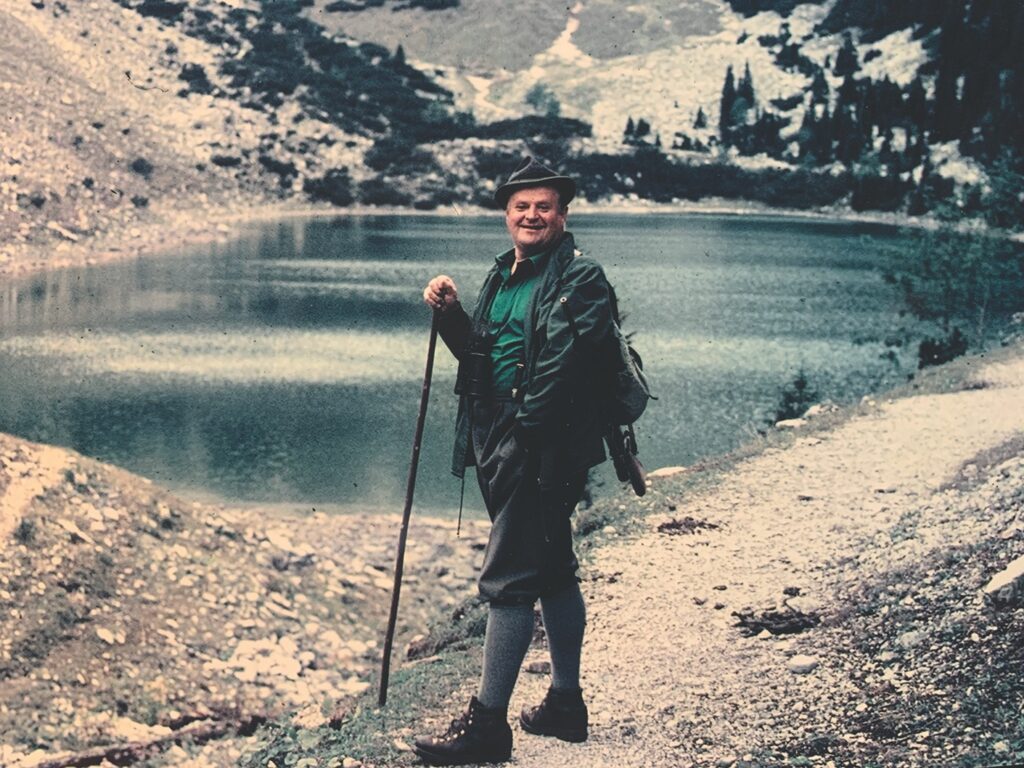

Edward T. Fortunato was stationed in Germany in 1972 and took the extensive tests to allow him to hunt there. He ended up taking a world-class chamois in the Alps south of Garmisch.

More than over 50 years later, whenever Fortunato looks at the chamois, it makes him smile. It is a symbol of “our family’s travels and adventure, the experience of the hunt, traditions, camaraderie, a love of nature and source of pride.”

I enrolled in the hunting classes required by the U.S. and German Status of Forces Agreement. To my surprise, the curriculum was not just firearm safety but a 132-page “Guide to Hunting In Germany.” It had 33 Sections of required learning prior to taking the written and shooting exam.

In Germany a hunter, or jaeger, must display in-depth knowledge of each animal’s habitat, food, breeding and all hunting protocols. The education is focused on conservation and the information covered is everything about game, hunting customs, tradition and culture.

Hunts are formal, organized and require either an invitation from a landowner or a lottery system. For big game such as red stag, fallow deer and chamois, the Army in cooperation with the German government established a lottery system. If chosen, you received a type and “Particular Quality of Animal” you could hunt. I wanted a chamois and knew there are three grades based on size, gender and age. I was fortunate to get selected for the top category, C1, which is a “Strong Buck” in its ninth year with horns scoring a minimum of 90 points by German measurement standards.

I was thrilled! I knew that chamois are found in the Alpine regions of Germany and that physical conditioning, specific gear and planning was in order. Soon after I was matched with a local alpine guide and wished Waidmannsheil, successful hunt by my fellow hunters. On a cold September day, I kissed my wife, son and daughter goodbye and headed out on my adventure.

I drove toward the southern region of the German Alps known south of Garmisch, near Austria. The foothills of the Alps began to give way to snowy mountain peaks. I had to maneuver hairpin turns with no guard rails. The views up and down the steep mountains were breathtaking and telling of the terrain I was about to hike.

This is a photo Fortunato took in 1972 of the steep and treacherous mountains south of Garmisch, Germany.

Local German hunting guide Hugo Held guided Ed to the chamois at about 7,000 feet in the Alps.

I met Hugo Held, my guide who at the time was twice my age. He was friendly and knowledgeable with a lifetime of experience. He explained we would set out on foot at first light and planned for a several-day hunt.

I woke before dawn and dressed in the traditional German hunting clothes comprised of gray lederhosen (knickers), thick long green wool socks and heavily cleated boots to maneuver the rough, steep terrain. I grabbed my binoculars, backpack and hunting gear for the day.

As dawn was breaking, Hugh and I headed out. It was near freezing and the sky was cold and gray. It had snowed lightly overnight and looking up, the rising sun was glistening on the high snow-covered peaks. Mountain fog hung low, making visibility difficult as we glassed for these small mountain goats which easily blend into the dull, rocky background. I was excited and thrilled to start the hunt as we began our morning of careful, steady climbing.

The climb was straight up and covered in slippery shale. We hiked for several hours and stopped to rest and catch our breath from time to time. The altitude made the physical effort even more challenging. Any concern I had about Hugo’s age quickly disappeared. I was more worried about me!

It was around 7,000 feet before Hugo put his arm up to signal, he had chamois in sight. I peered forward and saw four chamois 100-150 yards up the mountain. We quietly sunk to the ground to set up the shot. Chamois are known for their climbing ability, agility and speed. Any misstep or slip on the shale would result in them taking flight and disappearing into the crevices along the mountain. We glassed four chamois, with one displaying the age and trophy characteristics required of a C1 class that I was selected to hunt.

We laid in the snow, elbows on hard, cold shale, frozen breath in the air. The four chamois were in line left to right.

“Shoot the chamois second from the left,” said Hugo in German. Wanting to be certain, I repeated in my limited German, “You mean third from the right?”

“Richtig,” or, in English, correct, Hugo said.

I looked at the chamois through my scope. I took a deep breath, finger readied on the trigger, exhaled into the freezing air and squeezed. The shot echoed across the majestic mountains like a bolt of thunder, then perfectly silent as falling snow. A trail of my frozen breath hung in the air. It was a clean shot and the chamois dropped. I brushed off the snow and felt my heart beat harder as we hiked up the mountain.

As ritual dictates, the chamois was given the letzter bissen, or last bite, a small evergreen branch placed crosswise in its mouth as a token of respect. Hugo picked up the 65-pound animal by its hooves and placed in on my back. We began climbing down the mountain. Midway we stopped to rest at a sheltered camp to warm up. We grilled steaks and enjoyed a good German beer. Once warmed and refreshed we continued down recounting the details of the hunt. As is customary, the meat was given to Hugo, and I packed the trophy to take home. I felt like I had a new friend, and we shared a heartfelt goodbye.

Once back in Heidelberg, I found a taxidermist and had the chamois mounted. In the town of Nuremberg, a competition was conducted for trophies taken in 1972. Hunters participated from across Germany and entered their trophies according to their categories to be rated by the judges overnight. The next morning, I walked into the show room and to my surprise my chamois’ right antler was adorned with a gold oak leaf! The “Gold Leaf” meant my chamois was rated No. 1 in Germany that year! A few months later in Heidelberg, I entered another competition and won first prize, resulting in a gold medal draped around its neck.

Time went on as did my Army career with multiple moves, including one back to Heidelberg years later. The chamois, adorned with its two gold medals, was always prominently displayed. Explaining what a chamois is and where they hail from was a constant as everyone from friends to repairmen would inquire upon seeing it. In time it was joined by other North American and African game. It was the start of an impressive collection representing a lifelong love of the sport of hunting.

Yet, of all the trophies, there was nothing more poignant that symbolized my time in Europe, the majesty of the Alps and the memories of a hunt steeped in tradition, customs and ritual than that for the chamois.

A few years ago, my son, Ed, gifted me for Father’s Day the opportunity for an official SCI measurement. The chamois was part of his life growing up, and he remembered the day I brought it home. He knew it was ranked No. 1 in Germany in two competitions in the ’70s, and he was curious about its world ranking.

Ed contacted an SCI measurer who explained how to take a rough measurement to serve as a baseline. In a rather humorous effort, my wife did the rough measurements standing on a ladder and relayed them back to me. We called the SCI measurer who excitedly explained that I needed an official Master Measurer because if the rough score was even close to accurate, this chamois was in the SCI top 20! I was shocked and excited!

My son and I tracked down Bob Kern of the Hunting Consortium in Berryville, Virginia. Kern, a Certified Master Measurer, measured the chamois and submitted the results to the SCI Record Book office. I was later notified by them that the chamois’ official placement is ranked “Number 14 – Alpine Chamois” and was awarded an SCI gold medal! Out of curiosity we also looked at the recorded history and found that in 1972, my chamois was possibly ranked Number 5 in the world.

It is hard to explain how thrilled and astounded I was at the news. After all these years, this chamois, which had traveled around the world, represented a journey that only began that September day in 1972. For 50 years it was a constant presence in our family. Never in my wildest dreams did I think my chamois also a world record holder hiding in plain sight!

When a hunt is over in Germany, and the hunters bring their game together, each animal is lined up according to rank, which they are given based on breed. They are laid on their right sides, so their hearts are placed facing up toward heaven. Each animal has a specific song (a tote) which is played on a jagdhorn to honor the individual game. The last song is Halali, a sort of taps for the group. It is a moving, respectful experience I had with my fellow hunters on previous hunts. This hunt did not end with that ceremony as it was a single animal hunt, but in the still of that evening I could not help but hear the fading notes of Halali.

I walked away proud of this trophy and part of a unique experience, yet I had no idea what I had in my possession.

Over 50 years later, as I look at the chamois, it makes me smile. It has been a symbol in our home that has burned bright in my life as a constant reminder of our family’s travels and adventure, the experience of the hunt, traditions, camaraderie, a love of nature and source of pride.

Ret. Col. Edward T. Fortunato is an SCI National Capital Chapter member who lives in Fredericksburg, Virginia.